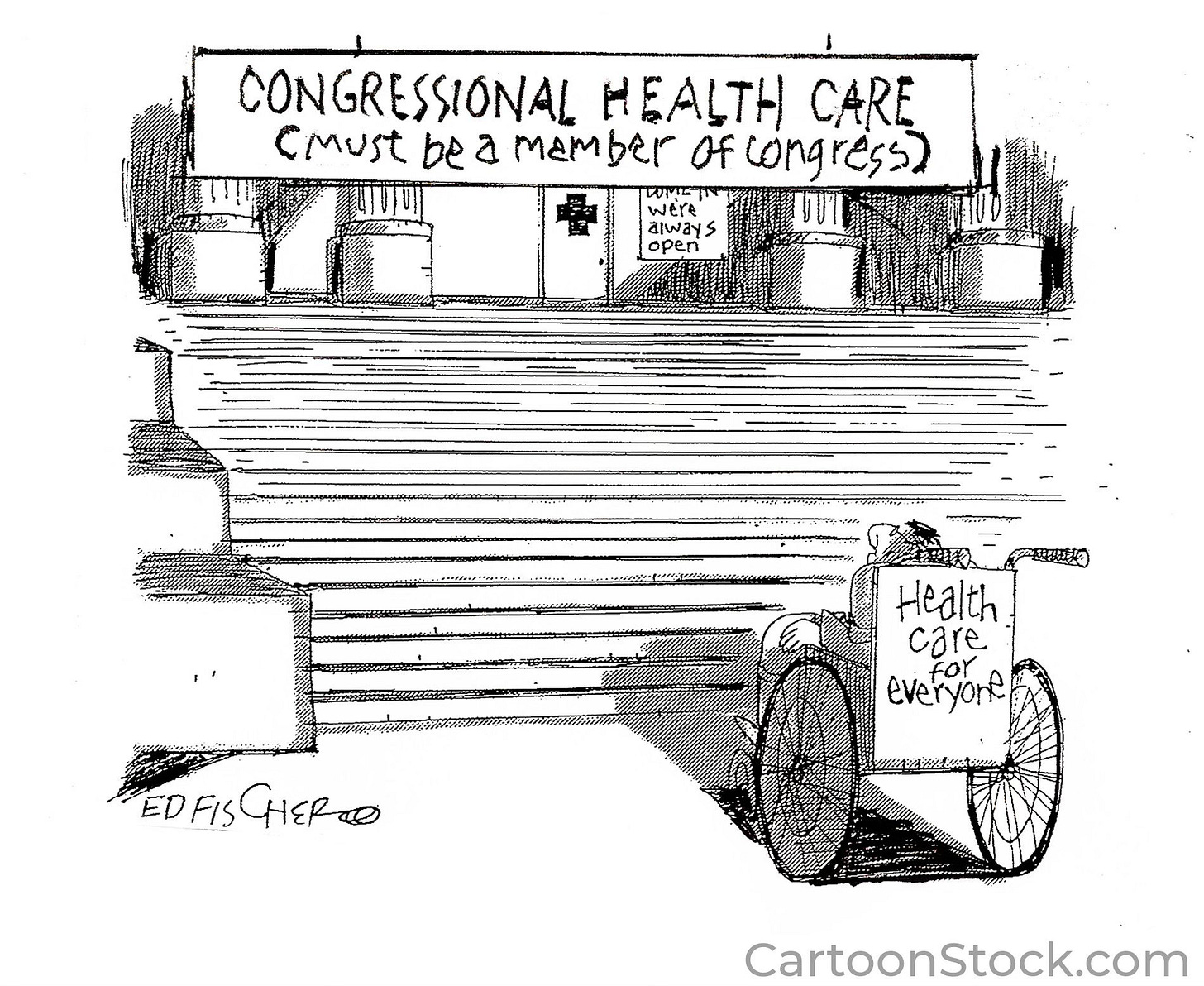

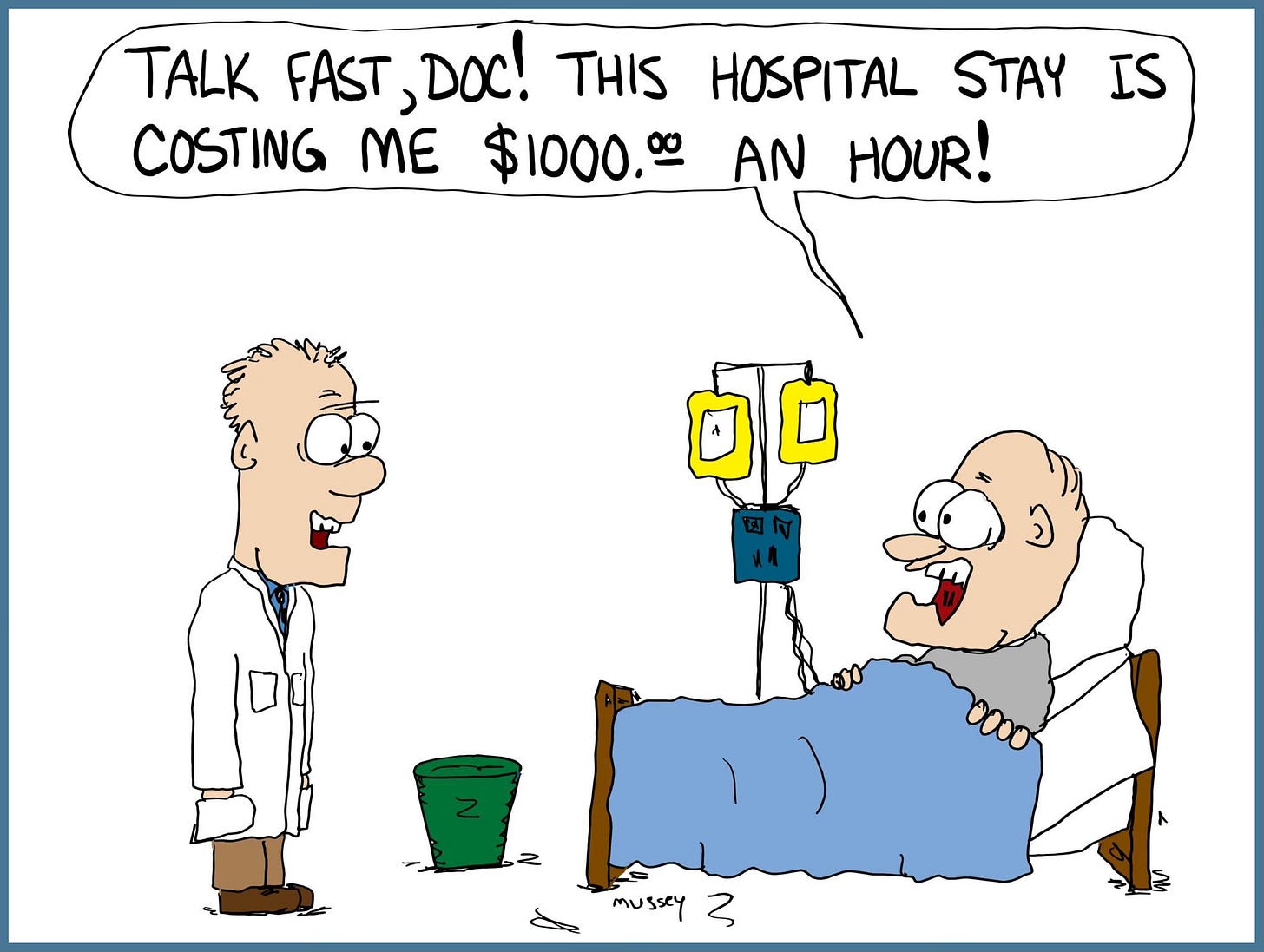

I’m doing background reading on the history of the economics of American health care for my next book and decided that reading could be part of an interesting series for my monthly Cancer Nursing Today column. Nurses get very little to no education on the financial side of U.S. health care and to me, that’s like sending troops into battle without teaching them about the real terrain they’ll be dealing with. Extending the metaphor, the nurses think they see a normal landscape of human vulnerability that their care will cover. There are obvious, visible challenges like steep climbs up, heavily wooded areas with limited visibility, etc. But unknown to them, the territory is dotted with quicksand, deep hidden crevasses, and invisible cliffs. Bridges that look solid can break unexpectedly and streams where one goes for clean water can suddenly run dry. Those moments of sudden, unforeseen crisis result from the exorbitant and often hidden costs endemic to our health care system. They enrich administrators and company owners, but leave patients and staff unsupported in a hostile environment, creating cynicism, moral distress and burnout.

It’s not a perfect metaphor, but the point is that nurses are trained to view the entire health care system as focused on one thing: helping patients. And nursing tends to attract people who embrace that idealism (physicians, too). However, the system is increasingly focused on an entirely different mission: making as much money as possible. Those missions are at odds. Of course health care systems and hospitals need to make money to stay in business, but when money becomes the mission, patient care, and support for staff, get less and less priority and everyone suffers as a result.

Also, many nurses are fresh out of college, which means they are young and healthy, and probably lack personal experience with worrying over their deductibles and co-pays, or being expected to pay large bills they cannot afford. I was older when I became a nurse, but still, my main experience with the health care system at that point only involved maternity care and maternity care was not struggling the way it is now. Only when I began taking care of really sick patients did I understand how much money factors into many people’s treatment and care decisions, including the patient who wanted there to be “death panels” that would kill him to avoid having his leukemia treatments bankrupt his family.

I went to the salt mines, reading and writing about Princeton Professor Paul Starr’s seminal book from 1982, The Social Transformation of American Medicine. Starr puts a lot of blame for how economically messed up our system is on the history of physicians working collectively to maximize their earnings and clinical autonomy. Let me be clear—he’s not blaming individual doctors and neither am I. I know many physicians who dislike what our health care system has become and feel as alienated from the patient-care mission as many nurses do. The point isn’t to blame, but to learn how we got here. It’s impossible to fix problems we don’t first understand.

Read on and leave a comment. As always, I’m interested.

Who Broke American Health Care?

Most nurses learn nothing in school about the internal workings of our health care system. One nursing school dean told me that they save that information for master’s level classes. But the majority of nurses never pursue further education and so miss out on understanding the complexity of health care financing and why the value of caring in health care has become subordinate to the value of making money. In this column, I try to rectify that gap in understanding. Helping nurses better understand the history of health care economics and structure may show nurses how hard it can be to fight for ourselves and our patients, and also why continuing that fight matters.

To tackle this topic, I return to an older, but essential book on the history of U.S. health care: Paul Starr’s The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry. First published in 1982, Starr’s book won the Pulitzer Prize and became, as a New York Times reviewer says in one of the book’s blurbs, “The definitive history of the medical profession in America.”

Nurses may be wondering why I’m discussing a book about doctors instead of nurses, or health care in general, but Starr’s book is important because of its focus on physicians. First, though, a confession: I was assigned this book in a college sociology class and never read it. It’s academic and highly detailed, and as a healthy 21-year-old who was not responsible for my own minimal health care costs, I had no context in which to place the book’s argument. Now, a nurse who’s seen patients and health care workers struggle with a system of bewildering intricacy and byzantine regulatory requirements, I want to grasp how the richest country in the world ended up with the most expensive health care on the planet that nevertheless provides worse outcomes than other countries where health care costs less.

In other news, I just finished a research trip to Portland, OR. It is truly wonderful to shadow within organizations that provide topnotch care despite the financial stress that typifies most of our health care. It’s not always easy for them, but they do it, and that does give me hope.

Hugs to all,

Theresa

I've read that antipathy toward socialized medicine began with public response to establishment of the Freedmen's Bureau after the Civil War. It was an easier sell to warn agains the evils of socialism than to advocate not helping destitute Black people. Atul Gawande wrote in a New Yorker article some years ago back when Obamacare was under consideration that when he asked his high school classmates in Athens, Ohio how they felt about universal access to healthcare,

they responded that they supported care for "deserving poor" but not for "undeserving poor" - and he posited that "undeserving poor" meant people of color. I believe racism persists as our national birth defect.

Thank you again for an insightful column. You are right, basic undergraduate education for nursing should include a course in health care economics and how health care is paid for. I never considered reimbursement issues until I became a discharge planning nurse and later a home care administrator. Even my Masters degree program did not include this type of course. Nurses need this knowledge to advocate for their patients. More nurses need to become politically involved and work for universal coverage. As far as doctors are concerned, I am hopeful. From the younger doctors I have encountered, including my son, I think that this new generation is interested in health care reform and ensuring that all receive needed health care. They are tired of the paperwork and fragmented, convoluted reimbursement system that they are forced to work with. I look forward to your next book. Enjoy the summer!