Be kind to our Language

Also, this Saturday, April 5, Nationwide Day of Protest: Hands Off...Medicaid, Medicare, Social Security, Federal Employees, all of it.

Timothy Snyder's 9th Lesson from On Tyranny

I’m putting on my English Professor hat for this column, but don’t worry, the nurse is still here, too: I’m thinking about words, but leading with empathy and common sense. This column was inspired by Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons From the Twentieth Century. Snyder is a professor of history at Yale and I just watched a great video of John Lithgow reading the “Twenty Lessons” from Snyder’s book (you can find the video here).

Lesson number 9—Be kind to our language—resonated with many of my own thoughts about how the language we, and the media, use to talk about politics and political issues, including health care, contributes to polarization and allows ignorance to spread without challenge. Here is Snyder’s lesson number 9:

Be kind to our language. “Avoid pronouncing the phrases everyone else does. Think up your own way of speaking, even if only to convey that thing you think everyone is saying. Make an effort to separate yourself from the internet. Read books.”

I discuss below four words and phrases it would behoove us all to think more about before using, two from health care and two others that address politics generally. This list is obviously not exhaustive. Please add your own words and phrases in the comments. The more language we have to be kind about, the better.

Words to think about before using:

Natural

Natural is being used to explain and defend why some parents choose not to vaccinate their children. According to parents opposed to vaccines for their children (but not for themselves, as I pointed in an earlier Substack) vaccines are not “natural” because they are made by humans, and instead of creating “natural” immunity like getting a disease does, they create “unnatural” immunity.

If you google this topic you will see many hits pointing out that the immunity created by vaccines is “natural” because it’s a function of the vaccinated individuals’s immune system. Getting a measles vaccine and getting the measles both produce natural immunity, but the vaccine creates that immunity without making the person sick, leaving them deaf or blind, or actually wrecking their immune system for years to come the way measles can.

Arguments about natural and unnatural immunity aside, let’s consider the word “natural” as it applies to disease. Ebola is natural and so is HIV. Tuberculosis, bubonic plague and smallpox are also natural. All infectious diseases are natural in the sense that they come from nature and have not been adulterated or changed by humans. How about guinea worm, which was endemic to several African countries and caused great pain when mature worms, that were usually a meter long, burst through the skin of infected people. To be eliminated, the worms had to be slowly and painfully wound around sticks, a process that could take weeks. (Jimmy Carter’s work through the Carter Center effectively eradicated guinea worm and you can read about that amazing humanitarian effort here.)

Would it be more “natural” to allow guinea worm infections to continue? Not to have figured out how to treat TB, which causes, inevitably, horrific deaths? To leave people vulnerable to the devastations of smallpox? I would hope that even the strongest opponent of childhood vaccines would answer “no” to each of those questions. Why then do those same parents privilege the naturalness of a disease like measles over the putative unnaturalness of vaccines? And why isn’t it seen as unnatural, in a different way, to willingly expose a child to pain and suffering when it could be avoided with a simple shot?

My tone may sound judgmental, but that’s not my intention. Instead, I’m trying to debunk the association between “natural” and “healthy.” The natural function of disease is to make us sick. The natural way of stopping that process from happening, of keeping us and our children healthy and well, is to stimulate the immune system to protect us from certain diseases in advance.

Medicaid and Medicare

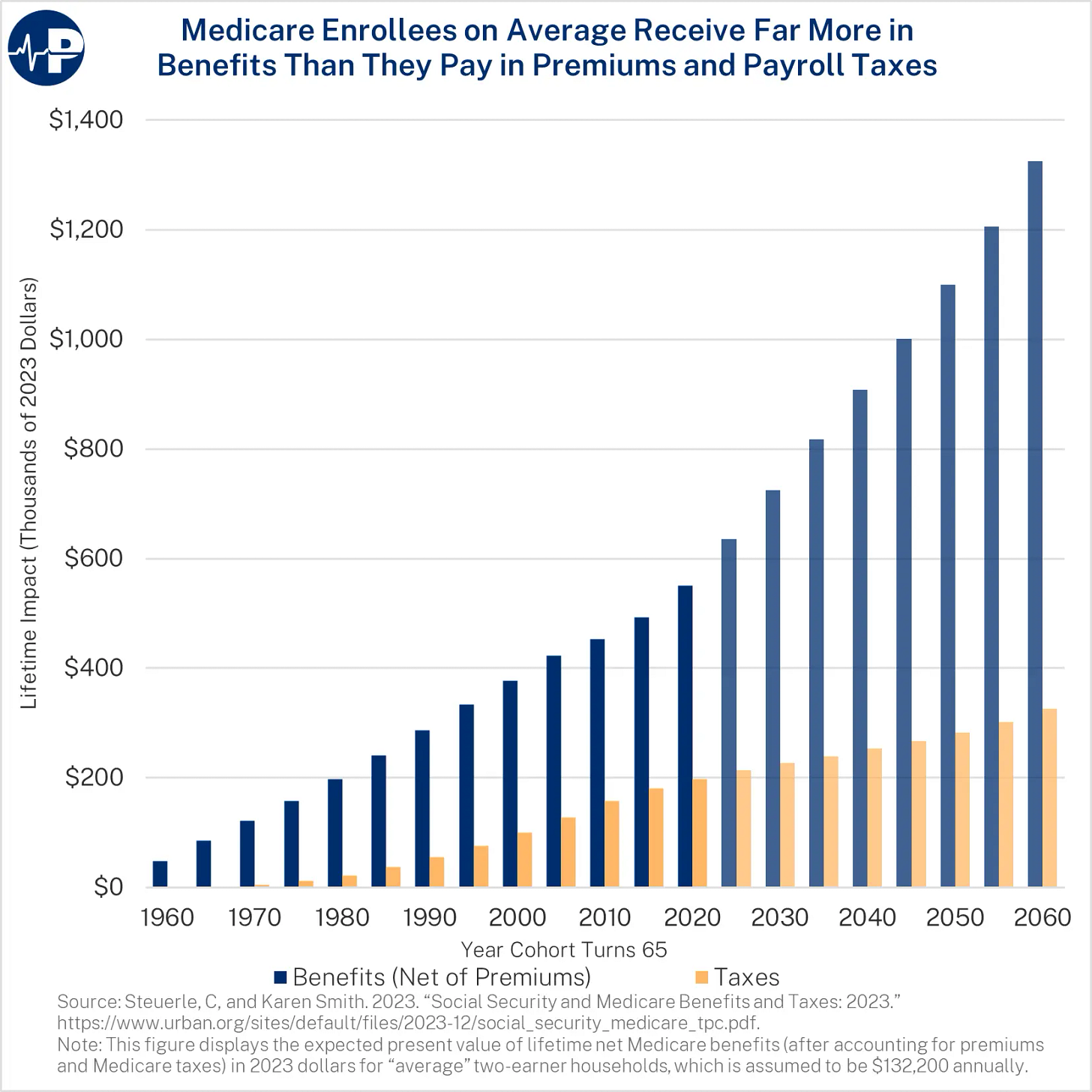

As Republicans continue to talk about severely cutting Medicaid, my daughter S. reminded me of how, several years ago, I explained the difference between Medicaid and Medicare to my kids. “Medic-aid,” I said is for poor people who are receiving help they haven’t necessarily earned. Aid implies charity with all of its negative implications of laziness and free loading. “Medi-care,” on the other hand, is for deserving senior citizens who have earned the right to free health care in their senior years by paying for it when they were employed. Except that is not quite true—most Medicare recipients receive more in benefits than they paid in while they were working. That is, older Americans who use Medicare are also receiving “charity.”

I think a lot about the level of cognitive dissonance revealed by people who protest government involvement in Medicare. It’s easy to mock such people as ignorant, but it’s more valuable to reflect on their need to believe that the health insurance they receive has nothing to do with the government. Those who look down their noses at Medicaid recipients while smugly enjoying their Medicare benefits embrace a similar kind of cognitive dissonance. “I’m not a freeloader—I earned this,” they think, when in reality that is probably not wholly true.

In the upcoming weeks when you hear conversations about Medicaid spending as the House and Senate try to come up with a budget, please keep in mind that aid and charity come in many forms and meet many different needs. About 42% of pregnancies in the U.S. are supported by Medicaid. Should those women and their children be cut off from health insurance and health care because they haven’t “earned” that financial support? Should elderly Americans be cut off from Medicare benefits once they reach the financial limit of what they actually paid into the system? Would it be so terrible to strive for a little more charity from and for all? Try to be kind to our language and each other when discussing Medicaid and Medicare.

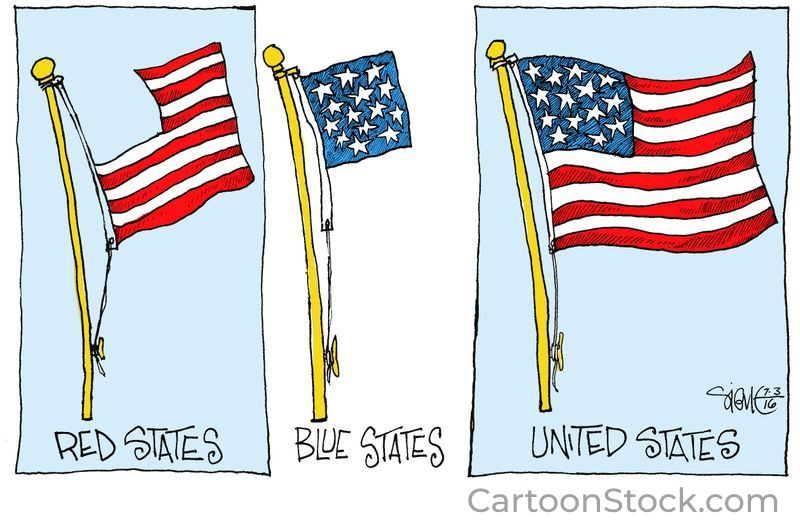

Red States and Blue States

My sense is that the media created this problem because it gives them easy visuals on election nights. Instead of describing states in terms of which candidate got the most votes, they became simply “red” or “blue.” The problem is that labeling states this way moves politics from the realm of people and ideas and into the realm of simplistic abstraction. Political questions get recast as tribalism devoid of stated meaning or values. You are your primary color, and no more.

To understand this problem better, think back to Dr. Suess. His books communicated complex themes using primary colors and simple, albeit clever, language. Calling U.S. states “red” and “blue” does the opposite of what Seuss did. It dumbs down our politics and also paints voters as uniform and lacking in agency, which can create feelings of helplessness. (However, the recent judicial election in Wisconsin showed that voter agency is alive and well. As you probably already know, Democrat Susan Crawford won a seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court by beating the Elon Musk-supported candidate, Brad Schimel, after Musk flagrantly tried to buy the election. Go Voters!)

I grew up in Springfield, Missouri, in the southern part of the state, in the Missouri Ozarks. Springfield is the National Headquarters of the Assemblies of God, a conservative evangelical branch of Christianity, and is also home to quite a few Southern Baptists. The concentration of conservative Christians in Springfield meant that I know what it is like to be surrounded by people much more conservative than I am, who actually put bumper stickers on their cars reading “God Loves You Missouri.” Over the past few years Missouri has grown even more conservative, to the point where I often don’t recognize the state I grew up in.

Still, then and now, there are plenty of Missourians who are not politically conservative, who believe in a less judgmental form of Christianity, if they identify as Christian at all, and who do not want Donald Trump and Elon Musk to destroy our government. Tagging the multiplicity of people who live and work in Missouri as “Red Staters” paints them as homogeneous and one-dimensional. I have been doing research in Missouri on palliative care and I can report that citizens of Missouri are the same as people everywhere.

Of course, describing populations of states as “tending to vote Republican” or “having a majority of registered voters who are Democrats” lacks the simplicity of labeling Americans with one of two primary colors, but that’s the point. Politics is complex, as are people. Our language needs to reflect that complexity if we want to have any hope of seeing each other as human beings and embracing another great principle of the United States: United We Stand.

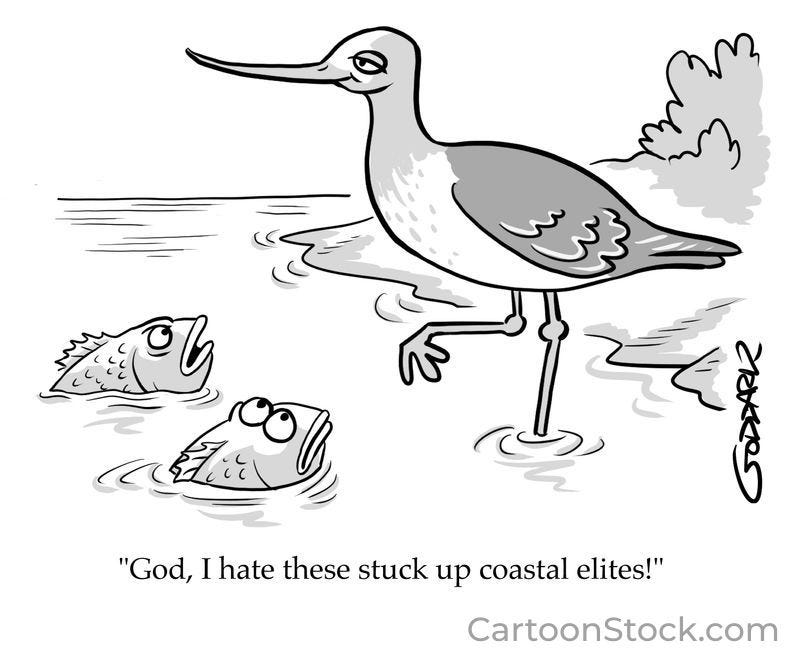

Elites

Conservatives use the word “Elites,” capital “E,” to denote liberal intellectuals and sneer at them while not specifying exactly who or what they are talking about. This is a logical fallacy known as a “persuasive definition,” which means that a commonly known word is given a new meaning for the sake of argument or persuasion while maintaining the emotion that attached to the word originally. That is, Americans in principle don’t like elites and elitism, so conservatives use the “Elites” brush to tar left-leaning thinkers and writers, rendering liberal arguments offensive regardless of their specific content or intent. More perniciously, this use of the word “Elites” obfuscates the real elites in the U.S.—the increasingly powerful and political billionaire class.

Conservative New York Times opinion columnists Bret Stephens and Ross Douthat often talk in dismissive terms about judgmental “Elites” without clarifying who they are referring to—Ivy League Professors? Liberal pundits?—or even making it clear that they are dismissing liberal viewpoints out of hand. This is intellectually lazy but also professionally dishonest. Anyone who is an opinion columnist for the NY Times is a member of the elite as the word is commonly understood. Having a paid platform in “the paper of record,” read by millions of people all over the world every day, is about as elite as print journalism gets. It’s rich—and I’m using that word deliberately—to have these columnists unironically denounce “Elites” or “Coastal Elites.” I mean, really?

But let’s also talk about the true elites in this country, beginning with Elon Musk, the richest man in the world, who has bought a President (Trump), runs the satellite systems that our defense relies on, is manically destroying our government, and tried to buy the recent judicial election in Wisconsin. Musk is the most elite of the elite by virtue of his wealth and global influence. Perhaps Douthat and Stephens could sneer at him, or another elite billionaire who has had an outside influence on American politics: Rupert Murdoch who founded Fox News and has a net worth of $21 billion. Then there’s Mark Zuckerberg, owner of Meta, and Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon. You know these names and their net worth (roughly) already; I’m stating the obvious to make what should be an obvious point—the true elites in the U.S. are the fantastically wealthy people who get richer and richer every year while middle class, and low-income Americans feel less and less secure about their livelihoods and lives. Also, in many cases the richest Americans are using their money to force our government to allow them to become even richer, no matter the cost to ordinary people. These people are the elite of our country because of the power their money gives them.

And then there’s Trump. The President of the United States is in a category of one in terms of being elite, and ever since taking office this January Trump has used his unique status and power to indiscriminately attack immigrants, federal employees, people who are trans, anyone in government who believes that diversity, equity and inclusion make our country stronger, and on and on and on. Trump epitomizes ruthless elitism. Remember that the next time you hear some conservative snarkily dismissing “Elites.”

Please share any other words we all should use kindly! As Corey Booker’s recent 25 hour filibister in the Senate showed, words matter.

Nationwide Day of Protest April 5

Tomorrow, Saturday April 5th, protests are taking place all over the country. I wish I could go to one, but I’m in Spain (which is lovely—I’m not complaining). If you’re interested, find out more here.

And hugs,

Theresa

Theresa, there was a lot to digest in your most recent post. I thought both the text and the illustrations you chose were perfectly paired to illustrate what you said. I was particularly interested in the part regarding elites, because that underlies much of the difficulty seen in accepting scientific facts: the mistaken believe that among Americans, there are those in the community with specialized knowledge, but since we are all "equal", that knowledge confers no credibility in discussing society-wide concerns. In my opinion, that represents a profound misunderstanding of the phrase "all men are created equal..."; we are not equal in terms of our learned experience or expertise, but rather America has no official lines of royalty. I have struggled with responding to my fellow citizens who use "equality" as a basis for ignoring people with specific expertise, but I also struggle with those experts who present knowledge in a way that is off-putting for people outside of their peer group. I guess the bottom line is that there is a great need for humility on the part of those individuals who present important information to the society at large, whether that's the science of vaccination, efforts at tobacco cessation, or recommended preventive health measures.

Sorry to ramble on a bit, but you have hit upon an important issue in the daily work of healthcare, and I appreciate the opportunity to comment further...

I loved this one, Theresa. Your first section, on “natural” takes me back to a college friend who studied biology. He taught me about the naturalistic fallacy—as you note just because something is natural doesn’t mean it is good! Sadly, RFK Jr seems incapable of grasping this concept.

The word I would love to see used less, or maybe used differently, is “success.” We have such a crabbed and narrow view of what constitutes success in our culture—a view that benefits big corporations who profit from overworking people desperate to succeed. I think we need to get rid of the belief that success equals money and status, and focus instead on the success of a happy, connected, and useful life.